Spermaceti organ

The spermaceti organ is an organ present in the heads of toothed whales of the superfamily Physeteroidea, in particular the sperm whale. This organ contains a waxy liquid called spermaceti and is involved in the generation of sound.[1]

Description

[edit]In the modern sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), this organ is far larger in proportion to the animal's body than what would be explained by simple allometry. Its evolution has caused changes in basal skull morphology, which may implicate that a trade-off was made that compromised the functionality of other features. The high investment in this organ suggests that it has some adaptive advantage, although its function isn't yet clearly understood.

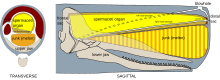

The spermaceti organ in sperm whales is shaped like an elongated barrel and sits on top of the whale's melon. Historically, the spermaceti oil found within it was used in a variety of products – including lamp oils, candles, and lubricants – providing the economic basis for the sperm whaling industry.[2] A sperm whale may contain as much as 1,900 L (420 imp gal; 500 US gal) of this oil.[3]

The morphology of the nasal complex is believed to be homologous in all of the echolocating Odontoceti (toothed whales), with the spermaceti organ homologous to the dorsal bursa in the dolphin.[4] The hypertrophied quality of the sperm whale's nose can be interpreted as an adaptation for deep diving unique to Physeteroidea.[5]

Hypotheses

[edit]Two main hypotheses exist for use of the spermaceti organ:

- It assists in controlling buoyancy by manipulating the spermaceti oil's temperature and, consequentially, its density, facilitating deep diving by cooling and surfacing by warming, as well as allowing the animal to remain motionless at great depth.

- It aids the whale in echolocation, by functioning as a form of sonar.

The first has been challenged by many authors, with the following points raised as problematic: the change in density that could be achieved by manipulation of spermaceti oil temperature would likely have a negligible impact on the animal's overall buoyancy; the anatomical features that would be needed for heat exchange with the spermaceti organ don't appear to be present; a mechanism of temperature regulation would necessitate high physical exertion while at great depth, which deep-diving animals tend to avoid; sperm whales appear to be highly active during dives, countering the suggestion that buoyancy manipulation would be advantageous because of its benefit in remaining motionless while diving; and the evolution of the spermaceti organ with buoyancy as a selective pressure would be very difficult and is unlikely due to the fact that the organ wouldn't have any impact on buoyancy until it became extremely large in proportion to the body.[6]

Thus, the hypothesis that the organ aids in echolocation is generally more accepted. Under this hypothesis, it assists in echolocation for foraging during deep dives, allowing the whale to manipulate the sound waves' direction and power to more easily detect prey.[7]

References

[edit]- ^

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Spermaceti organ". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Spermaceti organ". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- ^ Würsig, Bernd G; Jefferson, Thomas A; Schmidly, David J (2000). The marine mammals of the Gulf of Mexico (1 ed.). Texas A&M University Press.

- ^ Norris, Kenneth S.; Harvey, George W. (1972). "A Theory for the Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale (Physeter catodon L.)" (PDF). Animal Orientation and Navigation: 397–417.

- ^ Cranford, Ted W.; Amundin, Mats; Norris, Kenneth S. (1996). "Functional morphology and homology in the odontocete nasal complex: Implications for sound generation". Journal of Morphology. 228 (3): 223–285. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199606)228:3<223::AID-JMOR1>3.0.CO;2-3. ISSN 0362-2525.

- ^ Huggenberger, Stefan; et al. (6 Jul 2014). "The nose of the sperm whale: overviews of functional design, structural homologies and evolution" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 96 (4): 783–806. doi:10.1017/s0025315414001118. hdl:2117/97052. S2CID 27312770.

- ^ Whitehead, Hal (2003). Sperm whales: social evolution in the ocean. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "Sperm Whales' Amazing Adaptations". American Museum of Natural History.